by Dina Gerdeman

Many companies hand out awards such as "employee of the month," but do they work to motivate performance? Not really, says professor Ian Larkin. In fact, they may turn off your best employees altogether

More than 80 percent of companies dole out work-related awards like "employee of the month" or "top salesperson." Managers often view these awards as inexpensive ways to improve worker performance; many believe that when employees bask in the glow of corporate praise, they may even feel motivated to work harder over the long term.

But new research suggests that some awards may actually have the opposite effect, according to a recent paper called The Dirty Laundry of Employee Award Programs: Evidence from the Field, written by Harvard Business School Assistant Professor Ian Larkin, along with professor Lamar Pierce and doctoral student Timothy Gubler from the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis.

The researchers studied an attendance award program initiated by managers at one of the five commercial-industrial laundries owned by the same midwestern company. Perfect attendance was defined as not having any unexcused absences or tardy shift arrivals during the month.

The plant managers had all the right intentions when they implemented the award program. Absenteeism and tardiness costs US companies as much as $3 billion a year. And in the case of the laundry plant, one worker's tardiness or absence can affect another's productivity. If one team of workers falls behind on the job, for example, other workers down the line are left to sit idle.

STELLAR EMPLOYEES WHO PREVIOUSLY HAD EXCELLENT ATTENDANCE AND WERE HIGHLY PRODUCTIVE ENDED UP SUFFERING A 6 TO 8 PERCENT PRODUCTIVITY DECREASE

The plant's attendance award program began in March 2011 and continued for nine months. Employees with perfect attendance for a month, including no unexcused absences or tardy shift arrivals, were entered into a drawing to win a $75 gift card to a local restaurant or store; the winner's name was drawn at a meeting attended by all the employees. At the end of the sixth month, the plant manager held another drawing for a $100 gift card for all employees with perfect attendance records over the previous six months.

The program did produce one benefit the plant managers were looking for: it reduced the average level of tardiness and led to more punctual arrivals for the workers who participated.

AIRING DIRTY LAUNDRY

Yet when Larkin and his colleagues took a closer look at employee time sheets and records showing the amount of laundry that actually got done both before and after the program was introduced, they found that the plant—unlike the other four that didn't have an award program—experienced some problems:

- First, employees ended up "gaming" the program, showing up on time only when they were eligible for the award and, in some cases, calling in sick rather than reporting late. Most interestingly, workers were 50 percent more likely to have an unplanned "single absence" after the award was implemented, suggesting that employees who would otherwise have arrived to work tardy on a certain day might instead either call in sick to avoid disqualification or else simply stay home because they would be disqualified from the award regardless.

Also, while punctuality improved during the first few months of the program, old patterns of tardiness started to emerge in later months. And once employees became disqualified and the carrot of the award was out of their reach, their punctual behavior slipped back downhill. Larkin says this runs counter to what some people believe—that such an award program might instill a long-term pattern of on-time performance in workers.

The hope is that with the award "you get them to do what you want them to do in a habitual way," Larkin says. "But we can say it's the exact opposite. There was only a change in behavior while people were eligible for the award." - Second, and perhaps more significantly, stellar employees who previously had excellent attendance and were highly productive ended up suffering a 6 to 8 percent productivity decrease after the program was introduced. This suggests that these employees were actually turned off—and their motivation dropped—when the managers introduced awards for good behavior they were already exhibiting.

These workers may have believed that the award program was unfair; after all, they had been showing up to work on time before the attendance program, so they wondered why an award was necessary and why some employees who used to show up late were winning the award.

"The award demotivated these employees," says Larkin, who interviewed workers at the plant to gain additional insight. "People believed it was unfair to recognize people who only changed their behavior because of this award. They felt that 'I'm a hard worker, and now they're giving awards for something like attendance. What about me?' " - All in all, the award program actually led to a decrease in plant productivity by 1.4 percent, which added up to a cost of almost $1,500 a month for the plant.

"Having your top performers demotivated for all eight hours on the job ended up creating a much bigger productivity hit than having the extra five minutes of work from someone who came habitually late," Larkin says.

Ultimately, the researchers concluded that rewarding one behavior sometimes can "crowd out" intrinsic motivation in another.

REWARDS THAT WORK

Despite the fact that this particular award brought more harm than good, many other types of award incentives have proven beneficial for companies. But Larkin says corporate managers should manage them closely to make sure that employees aren't gaming the system and that the programs aren't fostering unintended negative effects.

"Many award programs have created value and are cost-effective for companies," he says. "Our paper shouldn't be taken as a blanket criticism of awards. You can't say awards are good or bad. It depends on how they're implemented."

This particular attendance award may have been especially flawed because rather than rewarding workers for exceptional performance, it rewarded them for fulfilling a basic job expectation.

"A lot of awards are focused on identifying people at the top of the class or people who went the extra mile," Larkin says. "This award did not recognize people who went above and beyond. It was an award for a behavior that employees should do."

Also, Larkin believes that awards are more effective when they recognize good behavior in the past, rather than behavior going forward. Plus awards for past performance aren't likely to see as much gaming, he says.

"It's motivational to hear that you've done a good job and are being recognized for doing the right thing," he says. "And it provides a good example for other people. People aren't being rewarded because they changed their behavior to match what the manager wanted or by gaming."

Larkin says that in the laundry study, the reward itself—gift cards—may have led to a higher likelihood of gaming. Sometimes it's better to keep money out of the deal.

"People respond very strongly to monetary incentives with this gaming mentality," he says. "When I talk to companies about award programs, I find myself telling them, 'Don't put in that $500 or the trip to the Bahamas.' It sounds like a nice thing to put in, but it also changes the psychological mindset people have."

Instead, Larkin says that companies may fare better just by giving people a nice plaque, sending an email to staff, or calling a meeting to recognize certain workers publicly in front of the whole crew.

"You can't put a price on that. The recognition of hearing you did a good job and that others are hearing about it is worth more than money."

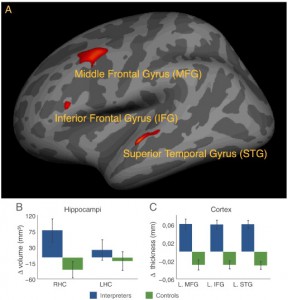

Learning New Languages Helps The Brain Grow

Learning New Languages Helps The Brain Grow